OFF TO SEE THE WIZARD – DICK MOORE

The rise and fall of a boxing master

By Jake Wegner

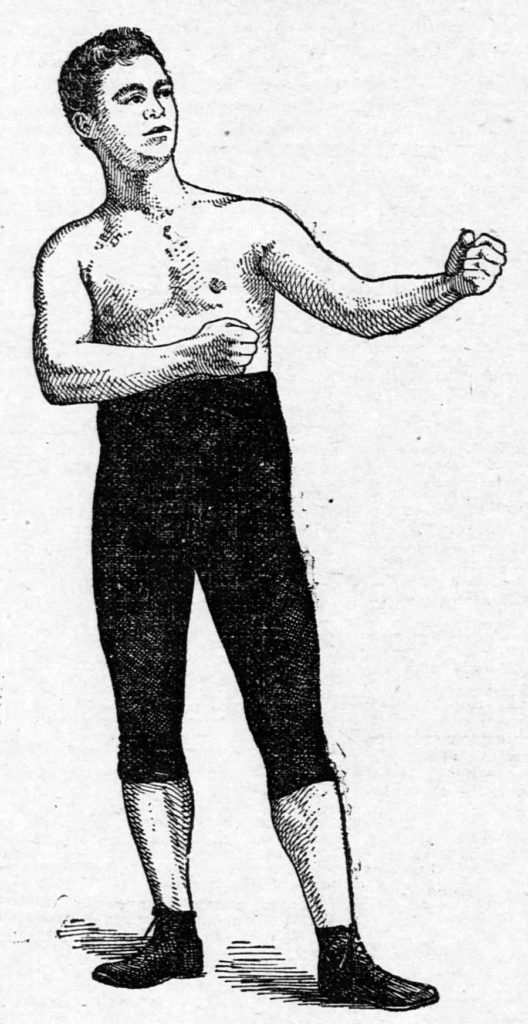

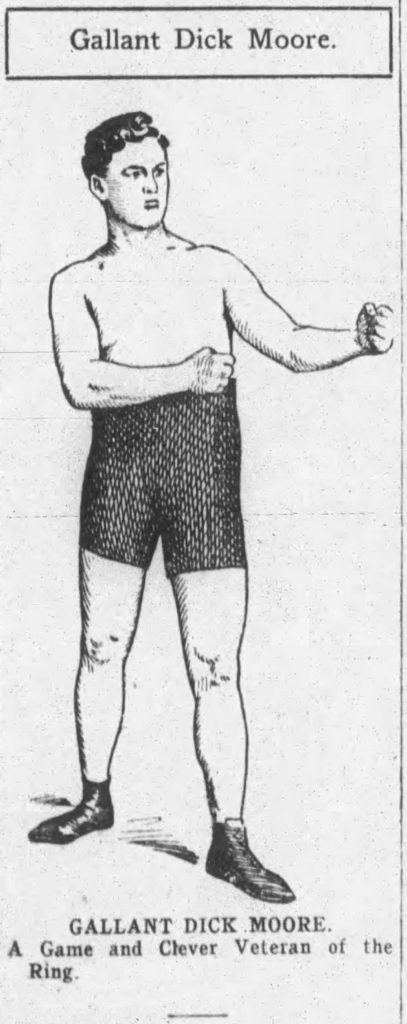

I had come across his name many times while researching the lives and careers of other 19th Century Minnesota prizefighters. Over and over I’d see his name in print, and with nice accolades beside it. “A boxing master,” one newspaper called him. “He has the moves and agility of James J. Corbett,” proclaimed another. Those were comments that caught my attention more than a little. But it was when I came across an 1893 newspaper article from the east coast, while Moore was campaigning out in Boston that really interrupted my research on my previous subject of fascination, and turned my sights on Mr. Moore. For this article rated this Saint Paul boxer as the 3rd best Middleweight…in the world, behind only Jim Hall, and champion, Bob Fitzsimmons…with some even predicting him to best both Hall and Fitzsimmons and to become the new world’s Middleweight Champion. It was just a matter of time, they said. A saucy prediction, to be sure. But what caught me even more was the fact that I could not find any boxing writers of the day who scoffed or even disputed this prediction. Moore was “it”. He was the coming man. It was then that I was hooked. Exactly who was this Dick Moore? This man whose right hand was so feared, and whose defense and speed was so revered that they compared him to Corbett? Often a quick glance was all Moore’s victims had before they went to sleep, and so surely I too, could afford his study more than a fleeting moment. I’m glad I did. For in the process of researching this boxing marvel, not only did I discover some 25 undocumented fights for his resume (which have been updated to boxrec), but I also discovered yet another fighter, whose name had been a secret to most, buried beneath more than century of yellowed newspapers. They called him “The Wizard” and “Gentleman Dick”. We call him our own.

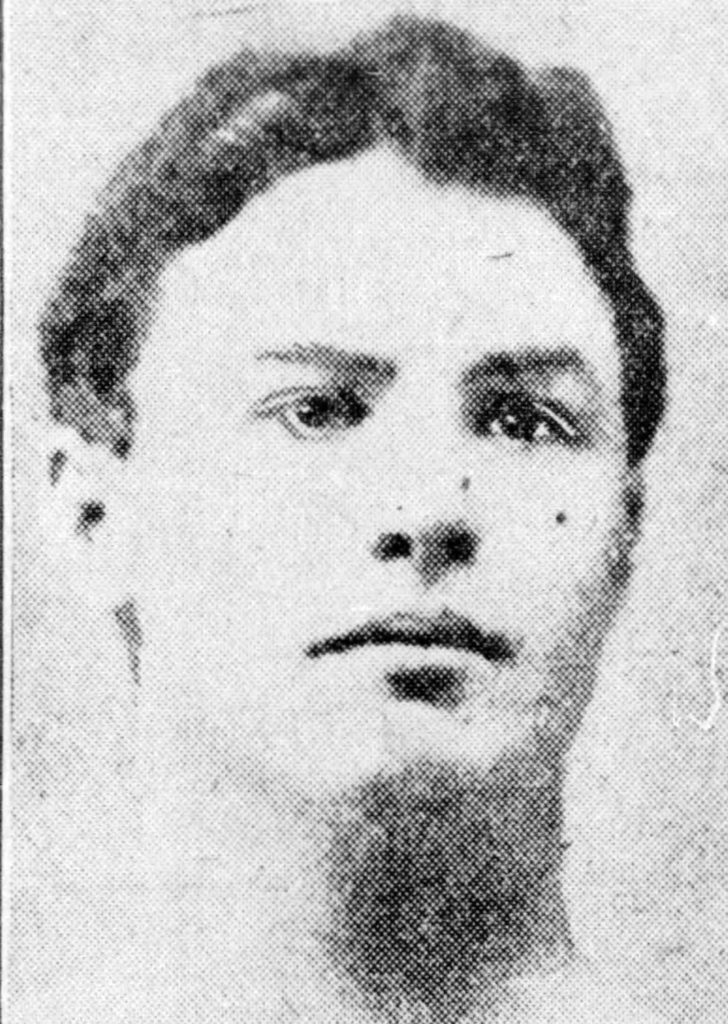

Richard Moore was born in 1871 in Tipperary, Ireland. His family had moved to the United States when Dick was just one year-old, choosing as so many of the Irish had, Saint Paul, Minnesota as their new home. Dick quickly took a liking to the action of pugilism and the purses that came with them. In his first year as an amateur, he placed 2nd in the Saint Paul Amateur Championships, losing a close decision to John Manning on June 23, 1888. He then turned professional under the management and training of Jack Herman. In a matter of a few weeks, he had registered five straight wins, including one particular viscous knockout victory over Paddy Dunn at the Theatre Comique in Minneapolis, which lasted less than a round. Dunn was out so cold, that his handlers thought he was dead. Dunn, himself, could not believe it, and accused Moore of fighting with “loaded” gloves. “No man can do that to me with normal gloves,” proclaimed Dunn to the papers. He pressed quickly for a rematch, getting what he wished for just a few days later in a private house in south Minneapolis. The result was the same…a 1st round KO for Moore, with Dunn once again lying unconscious.

Dick had a passion for learning the tricks of the game and began working as a sparring partner for a fellow Saint Paulite, and a mighty one at that—the Lightweight Champion of the Northwest, the great Danny Needham. Needham took a liking to the apt and willing young student, and offered to assist in his training duties; an offer Moore was all-too willing to accept. It is said that the tutelage of Danny Needham greatly accelerated the learning curve of young Moore; a fact not hard to conceive. But fighting skills were not the only thing that Needham taught Moore, as perhaps equally as important was conditioning, as Needham was already looked upon as one of the iron-men of the sport. By working out with Needham, Moore knew full-well how to train, but he also discovered just how much he hated it. Whereas Needham treasured training, Moore despised it. It is a well-documented fact throughout Moore’s long career just how many fights could have been won, were he in proper condition. This one dark trait would prove to be one of Moore’s key flaws in later years.

By the summer of 1889, Moore’s record was an admirable 10-0-3 (9 KO’s) and he was already a growing celebrity in Saint Paul circles. Saint Paul had long been looking for a man to best Minneapolis’ best fighter, Harris Martin, “The Black Pearl”. The Black Pearl was one of the best pound-for-pound fighters in the world, and was admired among both black and white America, and just happened to hail from Minneapolis. Even back in the 1800’s, Minneapolis and Saint Paul were fiercely rival cities. They hated one another and found competition even in the most miniscule of things. But pugilism was no minor thing. Not then, not now. Saint Paul had tried for years to produce a fighter capable of taking down the Pearl and taking over bragging rights. They thought that man was young Dick Moore. They believed (as many experts of the day did), that Moore’s agility and scientific boxing skills would overcome the Pearl’s muscle and power. But The Black Pearl was no ordinary fighter. In addition to his lofty record that only showed 1 loss out of some 50 or so fights, the Pearl was much more experienced in ring warfare. He was already billed as the 2nd best Middleweight in the world, and the Colored Middleweight Champion. Martin now wanted this fight with Moore to transcend the color line and to be for the Northwest Middleweight Championship—a title that was second in its day only to that of being the World’s Champion. The fight was a mismatch, with Moore getting knocked out in the 7th setto of a very one-sided affair. The Saint Paul factions refused to believe that Moore could be bested so easily, and demanded an immediate rematch. The result was even worse, with the referee stopping the fight at the end of the 4th round, out of fear for Moore’s life; and fights were rarely, if ever, stopped by the referee in those days. But Moore claimed that he had learned a lot in those fights, and would use those losses to his advantage in learning the fight game. He did.

After the two losses to The Black Pearl, Dick Moore went on a tear, traveling the country and facing many skilled fighters, going 5-0-2 before agreeing to face a man who he had hated for months—Jimmy Griffin. Jimmy Griffin was a very good, strong fighter. Very few of his fights have been discovered by boxrec, but papers of the day pegged him at 10-2, including a close fight with Danny Needham. In October of 1890, both he and Moore were drinking at Pat Killen’s Bar in Saint Paul, when an argument ensued and the two went at it. Both were a bloody mess at the conclusion and were also arrested and jailed for the incident. Moore’s hate for Griffin deepened and led to them squaring off in December. Moore beat Jimmy faster and more impressively than did Needham 2 years prior. Griffin could hardly lay a glove on his much faster opponent, as Dick cut him to pieces and knocked him out in just 2 heats. The papers all began calling him by the nickname of, “The Wizard” due to his clever ring agility and polished boxing skills. But there was a man in the crowd that night whose skills were above that of Moore’s. The one and only, Charley Kemmick. Kemmick was legendary in his own time, as no one wanted to fight him. He was so good in fact, that he played with his opponents and bet on which round he would take them out. He was according to the papers, the “uncrowned Welterweight champion of the world.” Kemmick, whose record is still being explored by historians, was reported to be undefeated throughout his entire career, with no one even coming close to beating him. When Kemmick retired, he was said to be a perfect 33-0. In any event, Moore wanted to fight him, but Kemmick seemed to be making excuse after excuse, and canceling one date after another with Moore, causing many to accuse Kemmick of ducking his younger adversary. But Kemmick was not ducking anyone. He was having breathing problems, and hiding a secret as to the true cause—Tuberculosis. Kemmick was a dying man and only when his health allowed, could he fight. Amidst all of this on again—off again banter between Kemmick and Moore, there was another fighter who was also gaining in popularity from Minnesota—Charley Johnson. Charley Johnson was a dirty fighter…a nasty fighter…but an extremely skilled fighter. His best punch was his right uppercut, and his chief skill was his timing and counterpunching abilities; of which, he was top-rate. He was 18-0-2 going into his fight with Moore, and the odds were pegged at even. The fight was billed to be a grudge fight, and one in which people literally fought one another in efforts to get tickets. The bout was to take place at the well-known Olympic Theater in Saint Paul on February 27, 1891. The fight was one that saw Dick bedazzle Johnson with his hand speed and his shifty footwork. Moore was a phantom in the fight, showing his full showcase of skills and teaching Johnson how to hit and not be hit. He had Johnson down 3 times and almost out in the 3rd round, but the bell saved Charley from what the papers called a certain knockout. Despite all of this, Mysterious Billy Smith, a friend of Johnson’s who ended up refereeing the fight, called the one-sided duel a Draw. The fans in attendance booed loudly. It was a robbery indeed. Dick Moore had showed one of the finer boxers in the country, how to box better, but still had to settle for a Draw verdict.

Shortly after the Johnson battle, Moore’s stock shot through the roof. He was now getting requests to box all over the country and many experts of the day had him pegged as one of the best coming men in the Middleweight division. Few disagreed. He knocked out Jack Stanley in just one round, and then went on to stop the highly regarded Frank Glover in 3 rounds. By then, Moore was 16-2-5, and starting to come into his own, when Charley Johnson came knocking once more. Moore had come to believe his own headlines at this point, and had put training in the background; thinking that his skills would be enough, as they so often had. Instead, Johnson pushed him to the limit and finally laid over a sleep-inducing blow in the 13th. Moore had lost a fight that he was expected to win. He was his own worst enemy in laying off the training, and took the loss hard. He would finish off the year by going 4-1, before being arrested for public drunkenness and assault after celebrating his victory over Paddy Cummings. This infraction was not Dick’s first, as he seemed to have an affinity for the bottle and was sentenced to a year banishment from Minnesota; a sentence that was very difficult for Dick, as he had been the primary care-taker of his aging mother for years and her primary source of financial support, as Dick’s brother, Joseph “Moldy” Moore, was a life-time criminal who was always in jail for various burglaries and could not be counted on.

Moore chose Chicago as his new base, and went 11-1 (8 KO’s) during his year of banishment from in 1892. After his sentence had expired, he immediately returned home to Minnesota, now sporting one of the better records in the nation on any Middleweight at 31-5-5, with 26 KO’s. He was quickly signed to fight “Cyclone” Harry Jackson from Detroit. That same night, the World’s Heavyweight Champion, James J. Corbett was in town and attended the fight at the Phoenix Athletic Club in Saint Paul. Corbett, always known for rarely handing out a compliment that wasn’t directed at himself, was so impressed with the science and skill shown by Moore (Moore stopped Jackson in the 3rd round), that he sent an invitation for Moore to join him for dinner that night, and later told reporters that Moore had all the makings of a champion, and that Moore was the only Middleweight that he had ever seen display the skills and science that he, himself, possessed. Quite an endorsement from a man not known for being liberal in his praise of fellow boxers. Stories of Moore’s meeting with Corbett ran in the papers and added to his already immense fame. In fact, no one enjoyed this meeting with Corbett more than Dick, as he began dressing like Corbett in fine clothes and carrying himself like a man of high-esteem and class. Dick instructed the newspaper reporters that though he was known far and wide as, “The Wizard of Boxing”, he would now prefer to be referenced as, “Gentleman Dick”, just as Corbett was called “Gentleman Jim”. His victory over Jackson helped lead to a showdown between Moore and Tommy Murray for the vacant Northwest Middleweight title, as that title was believed to be vacated when the Black Pearl was banned from Minnesota for a legal episode in 1891, and by 1893 the Pearl was believed to be retired as well. Murray and Moore fought to a 10 round Draw, and so no title was awarded. They had an immediate rematch with Moore battering his opponent so badly, that it was stopped in the 10th round, with Moore claiming the Northwest Middleweight title.

Just as Moore had lost only once in 1892, he carried that success with him and did not lose one single match in 1893, including big wins over George Kessler and Buffalo Costello and going 11-0-1 (7 KO’s); his record then was a dazzling 42-5-6 (33 KO’s) before facing one of the most feared men in the world in Dan Creedon, who was a perfect 17-0 with 13 KO’s, and was known as one of Australia’s premier fighters. It was a fight that saw Creedon throwing bombs and Moore using his agility and counterpunching skills and ended in a Draw. The fight had taken place out in Boston, where Dick had taken up residence in an effort to capture some major purses that the Easterners were offering to get a glimpse of “Gentleman Dick”, and he did not disappoint. Just before this match, he was married there to a Bostonian lady of high-class by the name of Mary O’Reagan. They married on January 31, 1894, and the news was reported from coast to coast. Moore also had a new manager in Boston by the name of Jack Merchant. Merchant was well-connected in the fight game on the East Coast, and it was big news when he had signed “Gentleman Dick” to a contract, as venues were sure to sell out. Dick was mentioned in many newspapers now, as the 3rd best Middleweight on the planet, behind only Jim Hall and the champion, Bob Fitzsimmons.

After the Creedon bout, Merchant got Dick a fight with another well-known boxer, and one that some thought would whip him—Professor Billy McCarthy. They were almost correct, as Dick was never big on training, and since being married was even less enthused about the thought of staying in shape. He would beat anyone with ease just on skill alone, thought Moore. His lack of conditioning would be a lesson that he would never learn, as McCarthy gave him hell from the opening bell and though it was clear that Dick was the better boxer of the two (and McCarthy was said to have fantastic boxing skills), Dick was huffing and puffing by the end of the 3rd round, with bystanders remarking of the loose flesh around his beltline. The fight would end in a Draw, but should have easily been a win for Dick, and Merchant let him know it.

Moore was taking on weight now, and people were noticing, even Merchant. He hired the best trainers on the coast to work with Dick; not to teach him to box, as there was little left to teach to the Wizard on that matter, but to keep him fit. But Dick resisted their advice and insisted on conditioning himself. Dan Creedon saw an opportunity to beat Moore and challenged him to a rematch. Moore was 157 pounds for the fight and did not look to be in shape. But this would be Moore’s new weight going forward, as he claimed that he could no longer make any less poundage. The fight was for the Middleweight Championships of both America and Australia. Creedon went to work on Moore’s body with reckless abandon, and Moore made him pay for getting so close, but only for a few rounds before Creedon’s monster blows began to take their toll on Dick. By the 8th round, Moore was a bloody mess, and so was Creedon, only the Australian had plenty left in the tank, and Moore was gasping. In the following round Creedon found an exasperated Moore and put him to sleep. This was in April of 1894. Moore was still only 23 years-old and considered to still be on the top of his game. But Merchant began noticing that Dick’s skills seemed to be slipping somewhat rapidly, and advised Moore to consider retiring. Moore would hear nothing of it. This was his living. He was bound to lose a few here and there. Everyone that made boxing their living, lost a few times a year; that’s part of the game. Besides, there were still large amounts of money to be made, and the name “Dick Moore” was a household name in the sporting community. Moore fired Merchant and continued his profession, taking on B.H. Benton as his full-time manager.

Moore and Benton traveled to Canada and then England, where Dick showed well and made a boatload of money in the process, as thousands flocked to see him fight. He returned to Boston in January of 1895. His record stood at 43-7-10 (33 KO’s). He beat Tom McCarthy over 10 rounds in Woburn, followed by a KO win over Jack Casey a few months later in Brooklyn, New York. He then returned to Boston and was surprisingly knocked out by Fred Morris in the 11th round. He then fought three straight Draws, including a 20 rounder with Billy Hennessey in August of 1895, before facing the infamous Kid McCoy. McCoy, one of boxing’s greatest all-time punchers, put Moore to sleep in the 6th round on September 2nd in Louisville. Moore then came home to Minnesota to face his former mentor in what was no doubt, sure to be the greatest local fight since Pat Killen had faced Patsy Cardiff almost a decade earlier, in fighting the great, Danny Needham. The fight news spread rapidly that the falcon had come home to face the falconer. The date was set for October 13th, and was creating a buzz that the Twin Cities had not felt in years. But prizefighting was supposed to be illegal in Minnesota at that time, though some got around the law by claiming their matches were “exhibitions of skill” and not “real fights”, though these excuses were always bold-faced lies. But now, the mayors of Minneapolis and Saint Paul intended to enforce the law and prevent the super-fight, which was leaked to be a “fight to the finish”. Ultimately, the fight was cancelled by the law, and both Moore and Needham were arrested and later released for conspiring to engage in an illegal prize fight.

Dejected by the lost opportunity for a large payday against Needham, Moore once again left his home state and went back East where over the next 6 months, he met with mixed results, going just 0-2-2 with 1 No-Contest. By now it was clear to all that Moore had lost “it”. He no longer seemed to possess the quickness and hand and foot that had previously made so many men look foolish and as if they did not even belong in the same prize ring. Gone too, was the chin that used to save him in the rare instances that his speed and agility failed him. But like so many fighters throughout boxing history, Moore simply refused to believe that he was all done. He was too young to be finished, he thought, and no one could tell the high-strung Irishman otherwise. From that day forward, Dick Moore’s once Hall of Fame career, began to slip away from him. His record was still an enviable 45-11-14 (34 KO’s), but he was no longer being called, “Gentleman Dick”, and no one at all was still calling him, “The Wizard”. He had not won a fight in over a year, but his name still drew big crowds, and all the boxing promoters knew it. Now that he was no longer as dangerous as he once was, managers and promoters began using him as stepping stone resume builder for their upcoming fighters to get a win over. And there were still fights that Dick pulled the upset or showed enough flashes of his former self to get a Draw and remain competitive, but he was for all practical purposes, finished. With that being said, Dick shocked everyone by staying 20 hard rounds with the great Tommy Ryan, and twice whipping the young rising star in Abe Ullman. It was these brief flashes of his former self that kept Dick going and allowed him to continue to earn large purses.

He began to slide rapidly in the late 1890’s. His boxing instincts were still there, but he had let his condition get so poor, that he eventually began campaigning as both a Light-Heavyweight and even a Heavyweight, and facing killers like Jack Root, Joe Choynski, and Barbados Joe Walcott. Newspapers around the country began to beg for his retirement, but he would not go, and to his detriment. The papers wrote about him in the past tense with phrases like, “Poor Dick Moore, once the best Middleweight in the world, should be sitting ringside as a guest of honor, but is instead, still plying his trade inside the prize rings,”. He did not officially hang up his gloves until 1905 at the age of 34, but it was an old 34. He later came out of retirement in 1918 for one fight in which he won by 3rd round KO. When including his newspaper decision fights, his record is officially 58 wins, 35 losses, 24 Draws, and 1 No-Contest for a total of 118 fights. After boxing, he and his wife took up residence in Yonkers, New York where Dick taught at a university as a professor. He died young at the age of 52 after a few hard battles with pneumonia and then a fatal heart attack on November 26, 1922.

The career of Dick Moore is one that no one remembers today. Yet at one point in time, the name Dick Moore was a household name and he rated as high as the #3 Middleweight in the world, with most experts of day predicting him to ascend to the Middleweight throne and knock off the great Bob Fitzsimmons. He is yet another gem in Minnesota history that any one of us local fans of the sport should be proud to learn of, as he is one of our own. A fighter, once one of the more dangerous men in his class, staying far too long, even past his own expiration date, until his skills began to sour, and his health and his legacy are both sealed in a dark fashion. We still see this phenomena occur today in boxing, don’t we? Had Dick Moore retired at the advice of his managers in 1894 or 1895, his name would be enshrined in the World Boxing Hall of Fame today, and his record would have been something to marvel at. But as it turns out, he stayed too long, and in doing so, ruined not only himself, but also his legacy. But does any of this take away from the skill-set that this past ring marvel once displayed? Not really. For when we analyze a particular fighter’s place in history, we tend to think of them at their peaks. No one remembers a faded Muhammad Ali losing to Trevor Berbick, a man he would have cut to pieces in his prime. The same can be said of any past great fighter. We remember them at their best, even if they insisted upon sticking around and taking unnecessary punishment and losses to lesser men. And if that’s true, and we all know that it is, then we as Minnesotan’s have yet another fantastic all-timer in the man that Corbett himself once marveled at. The man that was so good a boxer, so adroit in his skills, that he was once called, “The Wizard” by not only his peers, but also his opponents, for the magic he so often displayed in the prize ring. Dick Moore…Saint Paul’s grand magician.